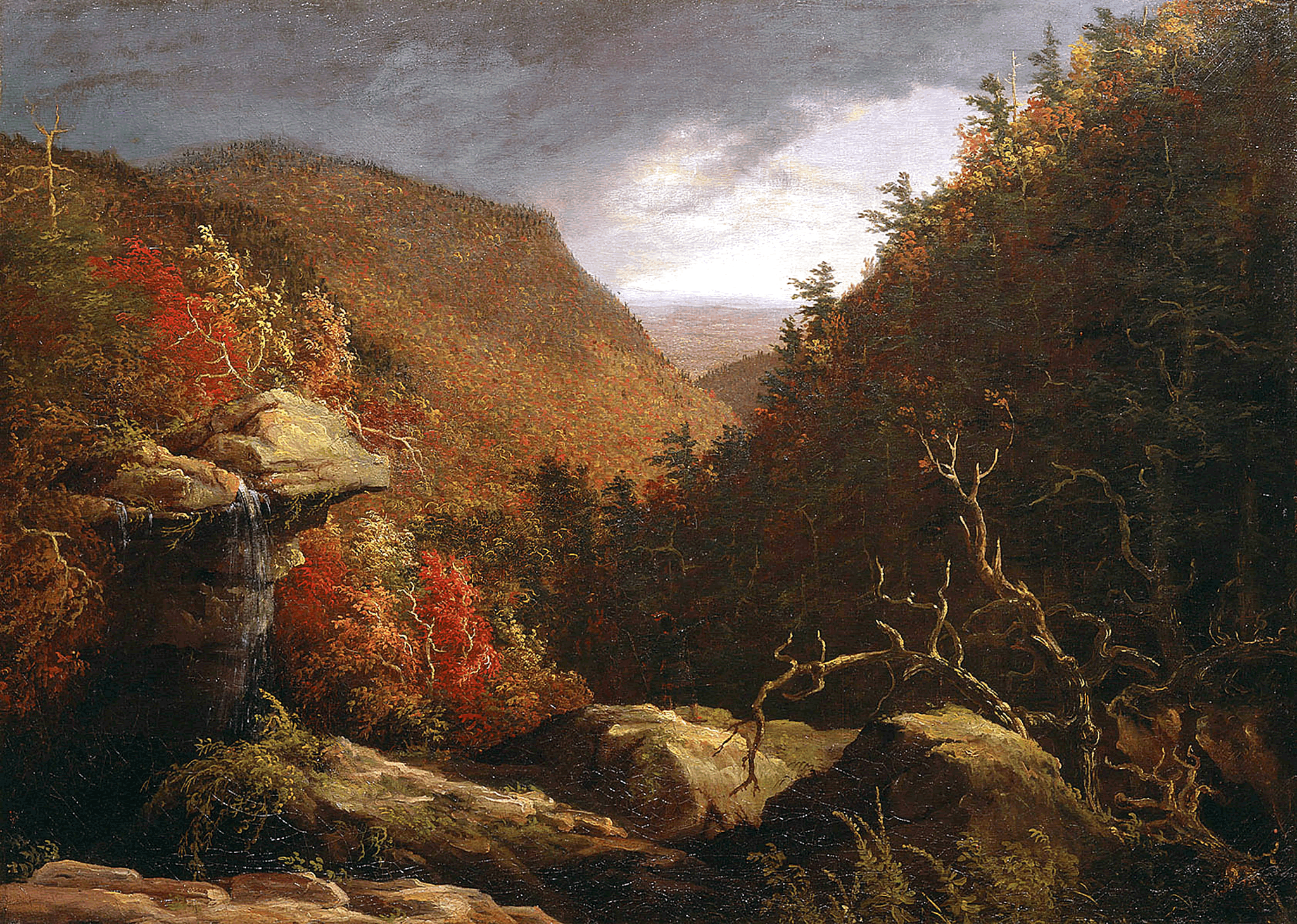

The Clove, Catskills

Thomas Cole, The Clove, Catskills, 1826, oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 35 1/8 in., New Britain Museum of American Art, Charles F. Smith Fund, 1945.22

About

Decode

Compare

Cole's Process

Cole's Words

Locate

About

A large gap in the Catskill Mountains, Kaaterskill Clove follows the course of Kaaterskill Creek from west to east. It was a center of international leather trade in the early nineteenth century. The tanning industry, dependant on hemlocks, brought about extensive deforestation in the Catskills during Cole's lifetime. To facilitate this trade, a turnpike through the Clove was created, providing not only tanners, but also artists and tourists, access to one of the finest vistas in the Catskill area. 1 Kaaterskill Clove was another of Cole's favorite places. He wrote in his journal of a trip to the Clove in 1838:

It was resolved that we should sleep, the next night, on High Peak. It would be tedious, perhaps, to describe, although anything but tedious was the ride to the Clove. The party was in the highest spirits... We entered the fine pass, where, on both hands, the mountains rise thousands of feet. The sun shone with golden splendour, and the huge precipices, above the village of Palensville, frowned over the valley like towers and battlements of Cyclopean structure. 2

In this 1827 painting—a view looking east from the top of Haines Falls—Cole chose not to depict such "golden splendour," but typical of his romantic imagination, he included a stormy sky to evoke the sublime.

1. Cole often achieved his greatest successes by painting scenes of autumn in the Catskills, because the brilliance of the colors impressed not only foreign audiences, but domestic critics and patrons as well.

2. This view looks east to the Hudson River Valley, with the Berkshire Mountains in the distance.

3. As a way of indicating natural cycles of growth and decay, Cole often framed his works with a dead or broken tree on the edge of the canvas.

4. As in Falls of the Kaaterskill, Cole used the lone figure of a Native American to lend an air of authenticity to the wild scene and to set it in a time before commercial exploitation of the wilderness.

5. Cole often used storm clouds to heighten drama. Here, the black storm clouds overhead, contrasted with the bright sky in the distance, represent the emotions associated with viewing a sublime scene: the sky simultaneously speaks of fear and hope, danger and exaltation.

Compare

Asher B. Durand, Kaaterskill Clove, oil on canvas, 1866, 38 ¼ x 60 in. The Century Association, New York, NY. View in Scrapbook

Durand's much later painting is a softer depiction of Kaaterskill Clove in the summer. Interestingly, it conveys more of a sense of the "golden splendour" that Cole described in his journal during his 1838 sketching trip to the Clove. The scene is more peaceful than Cole's more turbulent view, while the lack of any human figures in the foreground gives the spectator the sense of floating over the vista. Here, we see Durandexperimenting with a new style, now known as luminism, in which the painting is unified through soft forms and contours and enveloping atmospheric effects. 1

Process

...I never succeed in painting scenes, however beautiful, immediately on returning from them. I must wait for time to draw a veil over the common details, the unessential parts, which shall leave the great features, whether the beautifulor the sublime dominant in the mind. 1

Throughout his 1825 trip up the Hudson, Cole kept a sketchbook in which he jotted down ideas, assembled a list of patrons, and most importantly, sketched directly from nature. This was a significant departure from his approach of only a few years before, in which he taught himself to draw based on popular manuals—such as William Oram's Precepts and Observations on the Art of Colouring in Landscape Paintingof 1810 and Henry Williams's Elements of Drawing of 1818—that included step-by-step instructions for rendering simple objects. 2 Cole's early sketches, such as Sketch of Flowers, are highly stylized, yet they do demonstrate a distinct interest in nature, and there are many separate studies of various types of trees and flowers among these works.

When Cole began to draw en plein airin 1823, he once again created studies of various species of flora, as in Tree from Nature. Yet as Tracy Felker notes, they feel "stiff and awkward", 3 suggesting that the transition from instructional manual to direct observation of nature was a difficult one. However, the drawings do have a nascent expressiveness that is lacking in Cole's copies from illustrations in manuals. By the time Cole painted The Clove in 1827, his direct study of nature had come to inform his works masterfully. This was a remarkable achievement for a largely self-taught landscape artist.

Works

1. Thomas Cole, Sketch of Flowers, graphite on off-white paper, 1823, 9 ¼ x 7 ½ in. From "Sketchbook No. 1, Pitsburg, 1823." McKinney Library manuscript collection, Albany Institute of History and Art. View in Virtual Gallery

2. Thomas Cole, Tree From Nature, graphite, pen, and brown ink on off-white paper, 1823, 9 ¼ in x 7 ¾ in. Albany Institute of History and Art. Gift of Edith Cole (Mrs. Howard) Silberstein, great-granddaughter of the artist, 1965.68.1. View in Virtual Gallery

3. Thomas Cole, The Clove, Catskills, oil on canvas, 1827, 25 ¼ x 35 1/8 in. New Britain Museum of American Art. Charles F. Smith Fund, 1945.22.

Words

There is one season when the American forest surpasses all the world in gorgeousness—that is the autumnal; & then every hill and dale is riant in the luxury of color—every hue is there, from the liveliest green to deepest purple—from the most golden yellow to the intensest crimson. The artist looks despairingly upon the glowing landscape, and in the old world his truest imitations of the American forest, at this season, are called falsely bright, and scenes in Fairy Land. 1

Cole was not alone in despairing: when Jasper Cropsey first exhibited his painting Autumn—On the Hudson River in London, he sent for dried leaves from America to prove to European critics that he had indeed accurately depicted their colors.

"Written in Autumn"

Another year like a frail flower is bound

In time's sere withering aye to cling,

Eternity, thy shadowy temples round,

Like to the musick of a broken string

That ne'er can sound again, 'tis past and gone,

Its dying sweetness dwells within memory alone—Year after year with silent lapse fleet by;

Each seems more brief than that which went before;

The weeks of youth are years; but manhood's fly

On swifter wings, years seem but weeks, no more—

So glides a river through a thirsty land,

Wastes as it flows till lost amid the Desert sand.The green of Spring which melts the heart like love

Is faded long ago, the fiercer light

Of hues autumnal, fire the quivering grove,

And rainbow tints array the mountain-height—

A pomp there is, a glory on the hills

And gold and crimson stream reflected from the rills.But 'tis a dying pomp a gorgeous shroud

T' enwrap the lifeless year—I scarce forgive

The seeming mockery of death; but that aloud

A voice sounds through my soul—"All things live

To die and die to be renewed again,

Therefore we should rejoice at death and not complain."Catskill, October, 1837 2

The sky will next demand our attention. The soul of all scenery, in it are the fountains of light, and shade, and color. Whatever expression the sky takes, the features of the landscape are affected in unison, whether it be the serenity of the summer's blue, or the dark tumult of the storm. It is the sky that makes the earth so lovely at sunrise, and so splendid at sunset. In the one it breathes over the earth the crystal-like ether, in the other liquid gold... And if he who has travelled and observed the skies of other climes will spend a few months on the banks of the Hudson, he must be constrained to acknowledge that for variety and magnificence American skies are unsurpassed... Look at the heavens when the thunder shower has passed, and the sun stoops behind the western mountains—there the low purple clouds hang in festoons around the steeps—in the higher heaven are crimson bands interwoven with feathers of gold, fit for the wings of angels—and still above is spread that interminable field of ether, whose color is too beautiful to have a name. It is not in the summer only that American skies are beautiful; for the winter evening often comes robed in purple and gold, and in the westering sun the iced groves glitter as beneath a shower of diamonds—and through the twilight heaven innumerable stars shine with a purer light than summer ever knows. 3

Find it here.