The Voyage of Life Series Page

Childhood (First Set)

Youth (First Set)

Manhood (First Set)

Old Age (First Set)

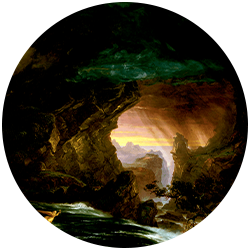

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life, 1839-1840, oil on canvas, 43 x 36 in., Munson, 55.105-8

In the late 1830s, Cole was intent on advancing the genre of landscape painting in a way that conveyed universal truths about human existence, religious faith, and the natural world. First conceived in 1836, the four pictures comprising The Voyage of Life: Childhood, Youth, Manhood, and Old Age fulfilled that aspiration. Cole may have derived the theme from any of a number of allegorical traditions, including John Bunyan’s popular narrative, Pilgrim’s Progress. Cole’s series traces the religious journey of an archetypal Everyman along the “River of Life.” The river flowing through each canvas reflects life’s twists and turns, while the season and time of day mirror each stage of life. Many of Cole’s poems and journal entries explore the idea of aging and the passing of time, and the notion of mortality seems to have preoccupied him from a relatively young age. In a poem written four years before he began sketching The Voyage of Life, Cole reflected, “The eager vessel flies the broken surge / The surge that it has broken—so my soul / Leaving the stormy past does onward urge / Its course through the wild waves that roll.” 1

Samuel Ward, a wealthy and deeply religious New York banker, agreed to pay Cole $5,000 for the completed series. Ward intended to hang the paintings in his art gallery, where his children and visitors could study them for their important moral lessons. Unfortunately, just as Cole’s patron Luman Reed had passed away while the artist was working on The Course of Empire four years earlier, Ward died before even half of the series was finished. Disappointed yet still committed to the project, Cole completed the series, exhibiting it in a one-man show at the National Academy of Design in 1840, despite legal troubles with Ward’s estate.

Cole feared for the fate of his masterwork after the untimely death of his patron, and before leaving for his second trip to Europe in 1841-42, he created tracings of The Voyage of Life so that he could paint a copy of the series in Rome. He exhibited this second set twice in Europe to much acclaim, although it failed to sell. The later works were then shown in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and again in New York, from 1843-46, accompanied by a program of Cole’s own interpretations of the paintings. 2

- Voyage of Life: Childhood (Second Set)

- Voyage of Life: Youth (Second Set)

- Voyage of Life: Manhood (Second Set)

- Voyage of Life: Old Age (Second Set)

By the mid-1850s, engravings of all four paintings in The Voyage of Life were widely available to the American public. 3 The moral message appealed to many Americans, who hung these inexpensive reproductions in their parlors. As a result of this wide distribution, Cole’s allegorical lessons were carried to many future generations. 4

COLE’S PROCESS:

Cole painted The Voyage of Life in his “Old Studio” at Cedar Grove. This space lay at the west end of a storehouse constructed in 1839 by the owner of the property, his wife’s “Uncle Sandy.” Cole wrote to his fellow artist Asher B. Durand that he was at work on “his great series” in this “temporary painting room” where “unplastered brick with the beams & timbers [are] seen on every hand.” 5 The studio, filled with Cole’s collection of art instruments and source materials—plaster casts, illustrated books and manuals, printed reproductions, paints, brushes, palettes and easels—has been restored and is now open to visitors at Cedar Grove (Thomas Cole’s Studio). Here Cole undertook a laborious process characteristic of art-making in the early nineteenth century. During this time of technological transformation, some art materials had begun to be available commercially. For example, by the 1830s, painters could purchase already-stretched and prepared canvases. Cole bought such goods from Edward Dechaux, a “colorman” firm in New York City. Previously, artists had to size their canvases with a solution of glue to strengthen the support; otherwise, the linseed oil used in mixing pigments would quickly destroy the canvases. Next, several applications of solid color (a ground, often a plain or tinted lead white) was necessary, followed by a long drying process. Colormen sold canvases already processed in this way, saving painters much time and effort, although Cole complained on occasion about the quality of these pre-prepared materials. 6

The convenient collapsible metal paint tube was invented in 1841 but not widely available until several years later. 7 Evidence from the collections at Cedar Grove suggests that Cole ground and mixed his own pigments (composed of minerals such as ochre, malachite, and azurite) in the traditional way. This process involved using a muller (glass bulbous instrument) on a flat marble grinding stone. The artist ground the colorful powders with a linseed oil binder in order to make the paint stable and viscous. Initially, a mortar and pestle might be employed to pulverize large chunks of pigment, but the muller was the artist’s most important grinding instrument.

COLE’S WORDS:

I have received a noble commission from Samuel Ward, a commission to paint a Series of Pictures the plan of which I conceived several years since & had an opportunity of presenting to him this Spring. The Subject is to be executed in four pictures about 6 ft. 6 in. or 7 ft. long each, and is entitled the Voyage of Life.

I earnestly & sincerely hope that I shall be able to execute the work in a manner worthy of Mr. Ward’s liberality and honourable to myself. The Subject is an allegorical one, but perfectly intelligible & I think capable to making a strong moral and religious impression. 8

I shall take the series to England & shall endeavour to dispose of them there. I have but little hope of doing so. The fashionable taste (if I may dignify it with such a name) is for works of another order[,] pictures without ideas, mere gaudy displays of colour & Chiaro Scuro without meaning, showy things for the eye. If I do not dispose of my pictures in England I must take them home & hang them in my own room & content myself with the conviction that the time will come when they will be more valued… 9