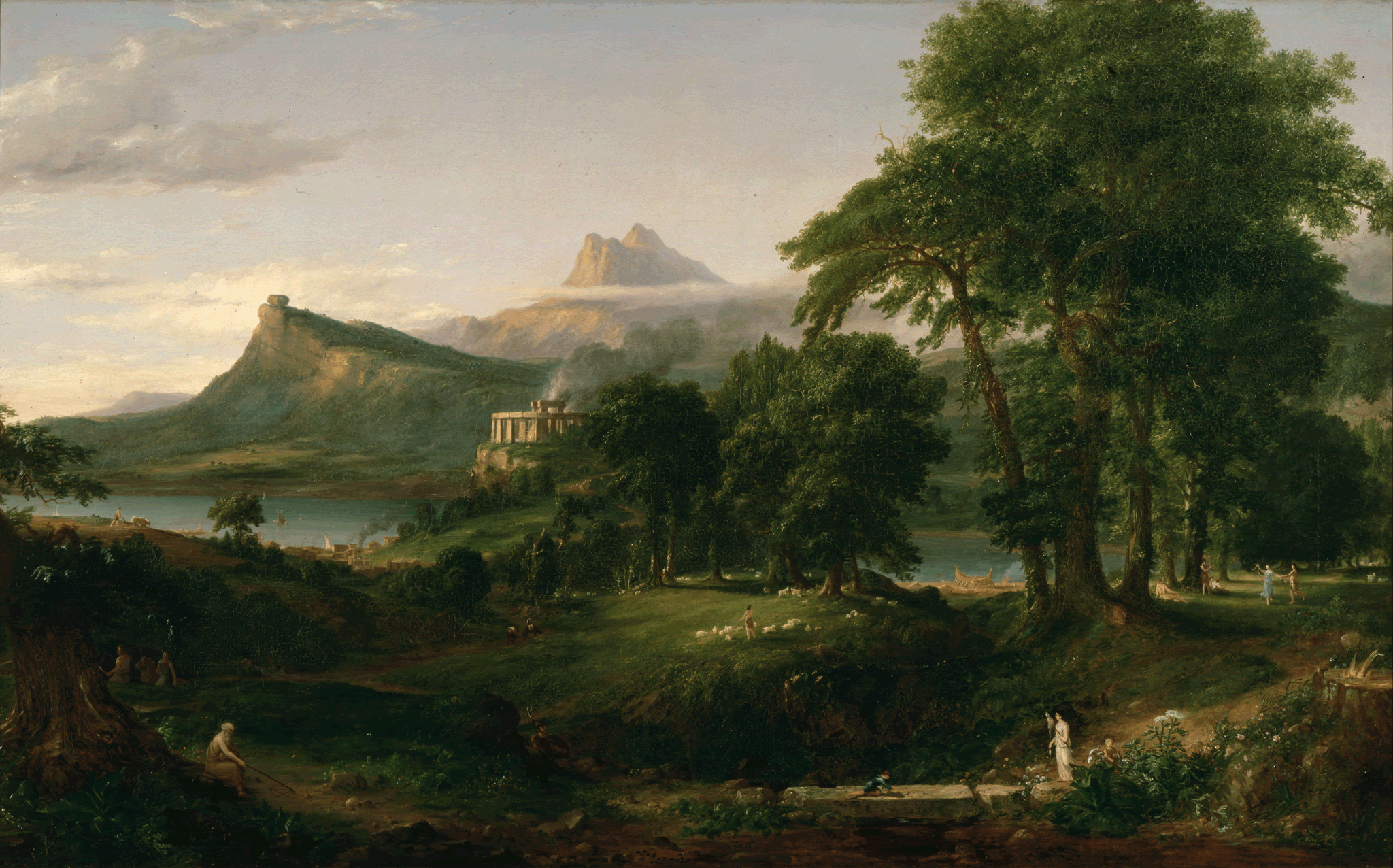

The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State

About

Decode

Compare

Cole's Process

Cole's Words

Locate

About

The second picture must be the pastoral state,—the day farther advanced—light clouds playing about the mountains—the scene partly cultivated—a rude village near the bay—small vessels in the harbour—groups of peasants either pursuing their labours or engaged in some simple amusement. The chiaroscuro must be of a milder character than in the previous scene, but yet have a fresh and breezy effect. 1

Decode

Mouse over the detail to view its caption, click it to zoom in, and use the reset button on the lower right to zoom back out.

1. The mountain first seen in The Savage State is now more subdued than in the initial painting of the series.

2. A Stonehenge-like structure signifies the beginning of monumental architecture and religion.

3. A farmer replaces the hunter-gather: a sign of permanent settlement.

4. An old man draws figures in the dirt, symbolizing the beginning of science and logic.

5. A young boy draws a primitive stick figure of the woman holding a spinning distaff, symbolizing the origins of drawing and painting. Look closely and you will see Cole’s initials on the bridge below the boy.

6. A tree stump, clearly cut by humans, is a disquieting harbinger of things to come. (Cole often used cut stumps to comment on the negative effects of civilization.)

7. Men and women dancing indicate the beginning of music.

8. A permanent settlement replaces the teepees of The Savage State.Smoke billowing out of the houses suggests human control over nature for domestic purposes.

9. Two mounted horsemen not only allude to human control over animals, but also to future military development.

10. The primitive canoes of The Savage State have evolved into more advanced ships, foreshadowing the beginnings of sea trade and imperial expansion.

11. A woman in classical drapery, carrying a spindle and distaff (a rod for winding thread), may be identified as the mythological figure Clotho, spinner of fate.

12. A boy tends his flock of sheep. The presence of sheep signifies a type of landscape depiction known as the pastoral.

13. The presence, left of center, of a soldier in armor presages the coming of military conflict.

Compare

Claude Gellée (Le Lorrain), The Village Fête (La Fête Villageoise), oil on canvas, 1639, 40 ½ x 53 1/5 in. The Louvre, Collection of Louis XIV, INV 4714. View in Scrapbook

The French landscapist Claude Gellée, commonly known as Claude Lorrain(1600-82), was another European master whose work Cole closely studied during his time in Europe. The Arcadian or Pastoral Statedemonstrates the influence of Claude's cultivated landscapes on Cole's work, with its light colors and soft brushwork. Like most ambitious landscape artists of his time, Cole was indebted to Claude's characteristic classical settings and distinctive compositional devices: balanced arrangements of trees and buildings framing a central landscape that recedes sinuously toward a light-suffused horizon. Claude's pictures provided much-imitated models for two categories of landscape painting: the beautiful and the pastoral. An American precedent for such graceful compositions is Washington Allston's Italian Landscape of 1814. Through an intermediary, Allston advised Cole particularly to seek out Claude's works for study while in Europe. In fact, when Cole was in Rome in 1832, he even worked in a painting room that was reportedly once occupied by Claude. By the 1840s, Cole actually came to be known as the "American Claude." 1

Process

Thomas Cole's artistic persona informed his ideas about the art-making process. As a young man, he fashioned an identity as a romantic artist, initially favoring wild sublime subjects and privileging untouched nature over civilization's institutions. Such predilections influenced his dress and other aspects of self-presentation. Cole roamed the wilderness in a black, flowing cape (see View of the Two Lakes and Mountain House). Although Cole mastered all the landscape conventions of his era—this particular painting in The Course of Empireseries shows a special facility with the pastoral mode—his self-conception remained tied to romantic ideals throughout his life. In contrast to Durand's calm portrait of Cole, the artist's own self-portrait and a late daguerreotype reveal a more intense, even brooding personality. These two works give evidence of Cole's romantic sensibility.

One important aspect of romanticismwas a notion of childhood as the origin of inherent creativity. As an artist who had little academic training, Cole probably conceived of his own talent in these terms. Although Cole included numerous self-references to his role as creator throughout the series of paintings in The Course of Empire, none is more intriguing than Cole's identification with the boy drawing in the foreground of The Pastoral State(zoom in to see the artist's initials below the boy).

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, artists sought to represent the "The Origins of Painting" or "The Origins of Drawing." They looked back to legends of natural-born geniuses, such as Giorgio Vasari's tale of the discovery of Giotto. According to Vasari, the Italian artist Cimabue recognized the amazing abilities of the unschooled Giotto as the young shepherd boy sketched on a rock in a pasture.

In 1827, Cole himself jotted down an idea for a work based on Vasari's legend. Parry speculates that the subject may have appealed to Cole because of his own "miraculous" discovery in 1825, which has itself become a potent legend in the history of American art. Reportedly, the older, well-established painter John Trumbull declared, on first encountering Cole's paintings: "This youth has done at once, and without instruction, what I cannot do after 50 years' practice." 1

By placing his initials under this boy who symbolizes—in Parry's words—the "infancy of the fine arts," Cole seems to underscore his own indwelling talent. On the other hand, close inspection of the boy's drawing reveals a comical stick figure of the woman holding a distaff. These childish scratches undercut the pretense of natural genius and may in fact hint at Cole's own insecurities as a figure painter.

Works

1. Thomas Cole, Self-Portrait, oil on canvas, c.1836, 17 ¾ x 22 in. New-York Historical Society. Purchase, The Watson Fund, 1964.41. View in Virtual Gallery

2. Matthew B. Brady, Daguerreotype of Thomas Cole, daguerreotype, c.1844-48. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC4-8981 DLC, DAG no. 057. View in Scrapbook

3. Asher B. Durand, Portrait of Thomas Cole, oil on canvas, 1838. Berkshire Museum. Gift of Zenas Crane. View in Scrapbook

4. Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State, oil on canvas, 1834, 39 ½ x 63 ½ in. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, 1858.2.

Words

The spring has come at last; we have had a few days the most celestial: the gentlest temperature, the purest air, sunshine without burning & breezes without chilliness, skies cloudless but soft. The mountains have taken their pearly hue & the streams leap & glitter as though some crystal mountain thawed beneath the sun; the bosomy hills heaving amid white & rosy blossoms blush in the light of day. The air is full of fragrance & music. O that this could endure & no poison of the mind fall into the cup! 1

Find it here.