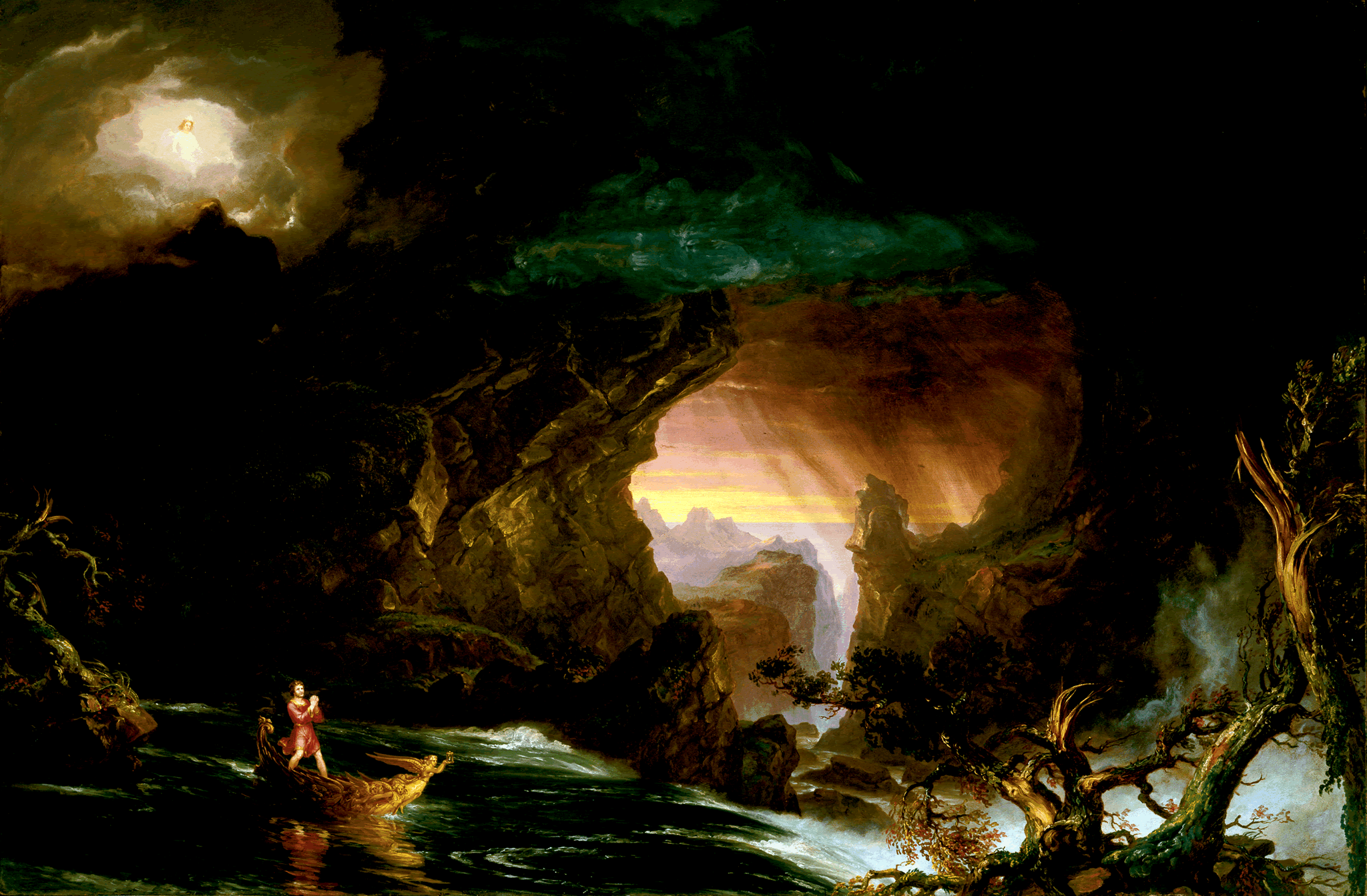

The Voyage of Life: Manhood (First Set)

About

Decode

Compare

Cole's Process

Cole's Words

Locate

About

MANHOOD.—Storm and cloud enshroud a rugged and dreary landscape. Bare impending precipices rise in the lurid light. The swollen stream rushes furiously down a dark ravine, whirling and foaming in its wild career, and speeding toward the Ocean, which is dimly seen through the mist and falling rain. The boat is there plunging amid the turbulent waters. The Voyager is now a man of middle age: the helm of the boat is gone, and he looks imploringly toward heaven, as if heaven's aid alone could save him from the perils that surround him. The Guardian Spirit calmly sits in the clouds, watching, with an air of solicitude, the affrighted Voyager: Demon forms are hovering in the air.

Trouble is characteristic of the period of Manhood. In childhood, there is no carking care: in youth, no despairing thought. It is only when experience has taught us the realities of the world, that we lift from our eyes the golden veil of early life; that we feel deep and abiding sorrow: and in the Picture, the gloomy, eclipse-like tone, the conflicting elements, the trees riven by tempest, are the allegory; and the Ocean, dimly seen, figures the end of life, which the Voyager is now approaching. The demon forms are Suicide, Intemperance and Murder, which are the temptations that beset men in their direst trouble. The upward and imploring look of the Voyager shows his dependence on a Superior Power; and thatfaith saves him from the destruction that seems inevitable. 1

Decode

Mouse over the detail to view its caption, click it to zoom in, and use the reset button on the lower right to zoom back out.

1. The youth has grown into an adult, who prays for guidance with an anguished look on his face.

2. Demons inhabit the clouds, representing Suicide, Intemperance, and Murder. Storm clouds reflect the tumult of manhood.

3. The angel now appears in the heavens, even further separated from the Voyager, and is no longer able to help him.

4. The hourglass continues to lose sand: the Voyager is running out of time.

5. The river turns violent and tumbles along large rocks, threatening to upturn the Voyager's ship and implying the precarious nature of adulthood.

6. The clear sky visible in the distance indicates hope and salvation; the sunset identifies the time of day as twilight.

7. Ragged and broken trees symbolize the treacherousness of the scene. The yellow and orange foliage, nearly gone, indicates the autumn season.

Compare

Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Manhood (Second Set), oil on canvas, 1842, 52 7/8 x 79 ¾ in. National Gallery of Art. Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, 1971.16.3. View in Virtual Gallery

Cole especially struggled with the composition of Manhood, and a reviewer, Thomas S. Cummings, singled this canvas out for criticism when the series was first exhibited: "with the figure in the third [painting] we are disposed to find fault; he seems to fall short of the grandeur of the subject, and of the reach of the artist, as displayed in the other pictures." 1 In reworking the second set of images while in Rome, Cole took the opportunity to make changes to Manhood. He moved the Voyager closer to the middle of the composition and opened up the vista behind the figure. These changes offer some relief from the unmitigated gloom of the first version of the scene. 2

Process

Cole experimented with many different compositions for the third painting of the series. In the earliest study, illustrated here, Cole intended for the painting to be a coastal scene, with stormy waves crashing against a cliff where the angel is perched. The Voyager clings for his life to the ship. In the second oil study, the waves are less intense, and the Voyager is seated, not standing, in the boat. The threatening demons appear for the first time in this work. The final oil study shows Cole working solely with the landscape. Here the design is closest to the final composition: the river turns into a waterfall at the right, and waves crash into a cliff with a broken tree. 1

Works

1. Thomas Cole, Study for The Voyage of Life: Manhood, oil on wooden panel, c. 1837-39, 12 x 13 5/8 in. Albany Institute of History and Art. View in Virtual Gallery

2. Thomas Cole, Compositional Sketch for The Voyage of Life: Manhood, oil on wooden panel, c. 1840, 11 x 16 ¾ in. Museum of Art, Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute. View in Virtual Gallery

3. Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Manhood (First Set), oil on canvas, 1840, 52 x 78 in. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, NY, 55.107.

Words

The latest footsteps of the year are now being impressed on the unstable, sandy beach of time—that shore which skirts the ocean of eternity. It is a narrow shore that man treads. Before him spread thick mists and darkness: and ever and anon, we hear the plunge of some one who has fallen into the deep. But let us not fear. It is the corporeal part of man that sinks. The soul soars over that vast sea, and finds a fitter dwelling place. 1

"The Dial"

Gray hairs, unwelcome monitors, begin

To mingle with the locks that shade my brow

And sadly warn me that I stand within

That pale uncertain called the middle age.

Upon the billow's head which soon must bow

I reel; and gaze into the depths where rage

No more the wars 'twixt Time and Life as now,

And gazing swift, descend towards that great Deep

Whose secrets the Almighty one doth keep.

I am as one on mighty errand bound

Uncertain is the distance—fixed the hour;

He stops to gaze upon the Dial's round

Trembling and earnest; when a rising cloud

Casts its oblivious shadow and no more

The gnomon tells us what he would know and loud

Thunders are heard and gathering tempests lower.

Lamenting misspent time he hastes away

And treads again the dim and dubious way.

1 February 1840 2

Find it here.