The Voyage of Life: Youth (First Set)

About

Decode

Compare

Cole's Process

Cole's Words

Locate

About

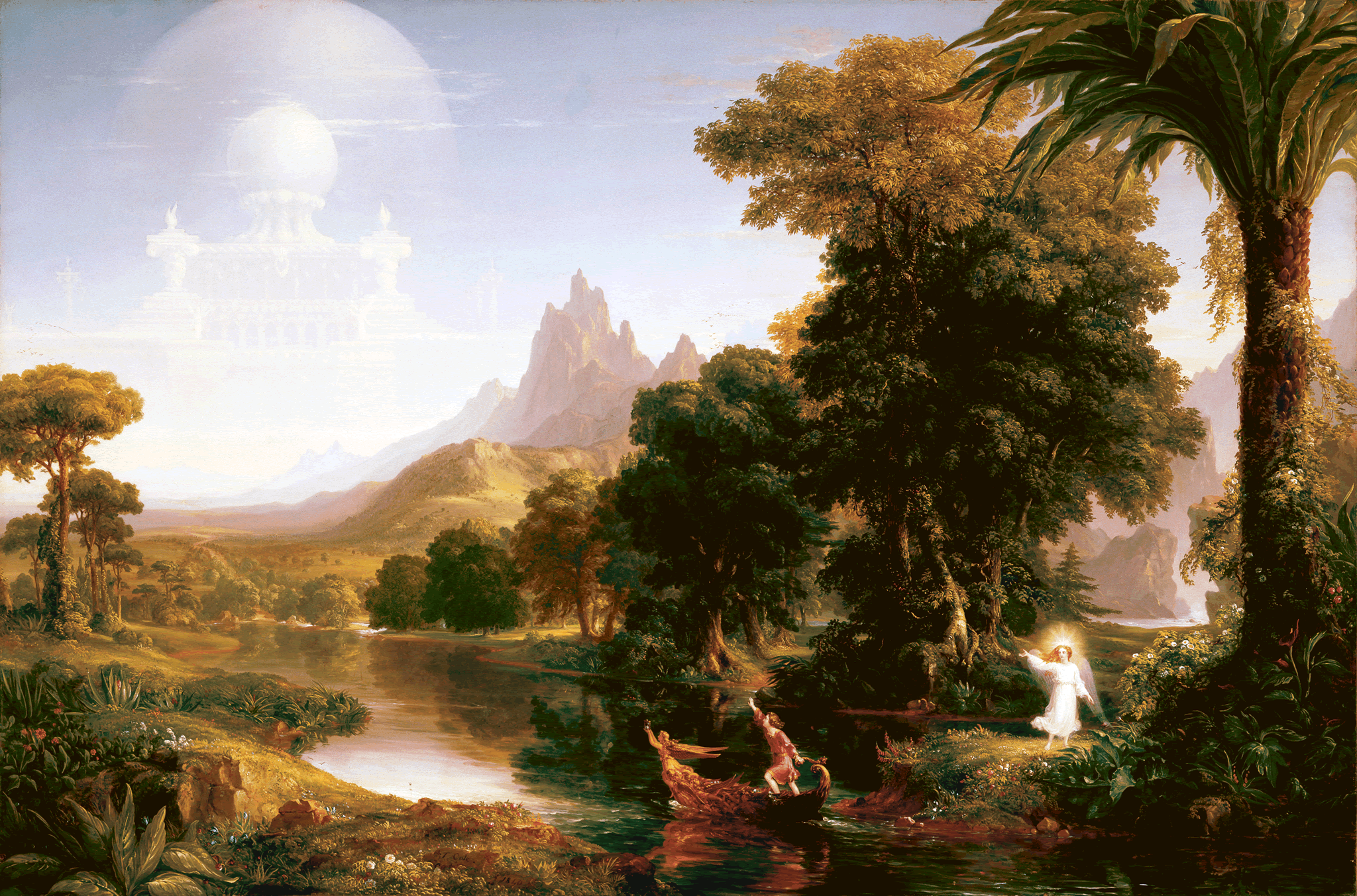

YOUTH.—The stream now pursues its course through a landscape of wider scope, and more diversified beauty. Trees of rich growth overshadow its banks, and verdant hills form the base of lofty mountains. The Infant of the former scene is become a Youth, on the verge of Manhood. He is now alone in the Boat, and takes the helm himself, and, in an attitude of confidence and eager expectation, gazes on a cloudy pile of Architecture, an air-built Castle, that rises dome above dome in the far-off blue sky. The Guardian Spirit stands upon the bank of the stream, and, with serious, yet benignant countenance, seems to be bidding the impetuous Voyager "God speed." The beautifulstream flows for a distance, directly toward the aerial palace, for a distance; but at length makes a sudden turn, and is seen in glimpses beneath the trees, until it at last descends with rapid current into a rocky ravine, where the Voyager will be found in the next picture. Over the remote hills, which seem to intercept the stream, and turn in from its hitherto direct course, a path is dimly seen, tending directly toward the cloudy Fabric, which is the object and desire of the Voyager.

The scenery of the picture—its clear stream, its lofty trees, its towering mountains, its unbounded distance, and transparent atmosphere—figure forth the romantic beauty of youthful imaginings, when the mind elevates the Mean and Common into the Magnificent, before experience teaches what is the Real. The gorgeous cloud-built palace, whose glorious domes seem yet but half revealed to the eye, growing more and more lofty as we gaze, is emblematic of the daydreams of youth, its aspirations after glory and fame; and the dimly-seen path would intimate that Youth, in its impetuous career, is forgetful that it is embarked on the Stream of Life, and that its current sweeps along with resistless force, and increases in swiftness, as it descends toward the great Ocean of Eternity. 1

Decode

Mouse over the detail to view its caption, click it to zoom in, and use the reset button on the lower right to zoom back out.

1. The infant Voyager has grown into a teenage boy, who confidently steers the golden boat towards his dreams, the castles in the sky.

2. Cole's critics found the change in the direction of the river unsettling, but the artist argued that the four paintings would otherwise be "monotonous," and noted that "there are many windings in the stream of life." Cole's reorientation of the river also makes for a more satisfying visual arrangement of the pictures.

3. Cole often referred to youthful dreams and aspirations as "castles in the clouds."

4. The hourglass has lost sand, indicating the passage of time.

5. The guardian angel has exited the boat, stands on the riverbank, and gestures towards the Voyager with a troubled look.

6. Lush varieties of vegetation identify the season as summer, while the bright sunlight confirms the time of day as noon.

7. The river suddenly passes a rocky ravine and picks up speed, foreshadowing the turbulence of Manhood.

Compare

James Smillie, The Voyage of Life: Youth, hand-colored engraving and etching after Thomas Cole, 1850, 15 3/16 x 22 11/16 in. Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, gift of the estate of Matthew Vassar, X.153. View in Scrapbook

After Cole's unexpected death in February 1848, the reputation of The Voyage of Life increased dramatically, and the Ward family was able to sell it to the American Art-Union only a few months after the artist's passing. This organization promoted American art by buying works and distributing them to its members via a lottery. Art-Unionmembers also received engraved reproductions of significant American paintings. Youth—always the most popular of the four paintings—was selected as an offering for a print edition of 20,000. The Engraving Committee engaged James Smillie, "believing him to be superior to any other artist in the country in this department." The fact that they agreed to pay Smillie an astonishing $2500 to reproduce Cole's painting underscores how important this commission was in promoting their organization. Eventually, Smilliemade prints of the other three pictures as well, and it was primarily these engraved images that made The Voyage of Life famous throughout America. 1

In the 1850s, the original paintings graced the walls of the Abbott's Collegiate Institution for Young Ladies in New York City (a pioneering precursor to Vassar College), demonstrating how The Voyage of Life was thought to be appropriate for a young woman's artistic and moral education. In fact, a replica of Youth is in the Vassar College collection, from the estate of the founder. But by the late nineteenth century, Cole's allegorical works had fallen out of favor with the elite and had become symbols of lowbrow taste. Edith Wharton's character, Lily Bart, scorns Cole's series in The House of Mirth(1905):

Lily knew people who 'lived like pigs,' and their appearance and surroundings justified her mother's repugnance to that form of existence. They were mostly cousins, who inhabited dingy houses with engravings from Cole's "Voyage of Life" on the drawing-room walls, and slatternly parlour-maids who said, 'I'll go and see' to visitors calling at an hour when all right-minded persons are conventionally if not actually out. 2

The Voyage of Life's popular appeal persisted well into the twentieth century, however, and appeared in a surprising context: as part of the set decor for an early "talking picture," The Jazz Singer (1927). In a key scene, a cantor's son turned Broadway entertainer has a tearful reunion with his mother. On the living room wall is a reproduction of Cole's The Voyage of Life: Youth. With renewed interest in the Hudson River School—and Cole's work in particular—in the second half of the twentieth century, The Voyage of Life was restored to its status as one of the key landmarks in American art.

Process

These sketches in oil and graphite demonstrate the process by which Cole created the figures in The Voyage of Life. Cole’s limited experience in drawing from live models no doubt hindered his ability to render the human form. As a largely self-taught figure painter, Cole did not have many opportunities to study human anatomy—unlike many of his contemporaries, who had undertaken full courses of study at fine arts academies. As a result, human figures and facial expressions often eluded him. In a letter to Cornelius Ver Bryck of 1840, he wrote:

You ask me how the Voyage of Life is progressing. The Angel’s face has given me a great deal of trouble. Angels’ visits to me are really so few and far between that I forget their features. Sometimes the expression would be sulky, sometimes cross, and sometimes silly. I have at length, finished one which I suppose will be found a compound of all the expressions of which I have spoken. But I will not disparage myself. I hope the picture is the most complete one I have ever painted. I should be happy to have you see it. I want other eyes: mine are accustomed to the picture. 1

In these numerous sketches, Cole reworked the faces and figures of the Angel and the Youth many times until at last he was satisfied with their appearance. 2

Works

1. Thomas Cole, Figure Study for The Voyage of Life: Youth, oil and graphite on canvas, 1839-40, 25 ¼ x 20 ¾ in. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, NY, 2001.41.1. View in Virtual Gallery

2. Thomas Cole, Standing Classical Figure, graphite pencil on yellow beige tracing paper, c. 1839-40, 7 3/8 x 4 in. Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, William H. Murphy Fund, 39.516. View in Virtual Gallery

3. Thomas Cole, Study for the Guardian Angel in The Voyage of Life: Youth, oil on canvas, c. 1839-40, 10 ¾ & 8 ¼ in. Collection of Mr. John M. Bransten, San Francisco, CA. View in Virtual Gallery

4. Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life: Youth (First Set), oil on canvas, 1840, 52 ½ x 78 ½ in. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, NY, 55.106.

Words

There are many windings in the stream of life, and on this idea I have proceeded. Its course towards the Ocean of Eternity we all know to be certain, but not direct. Each picture I have wished to make a sort of antithesis to the other, thereby the more fully to illustrate the changeable tenor of our mortal existence. I am convinced the opinion of spectators will be various on the subject of the direction of the stream. This I have gathered from remarks already made. That which you have thought might be a defect, has been considered a beauty. 1

I am still a Youth in imagination & build castles still. They will crumble away most likely but if I can find by groping amid the ruins some bits of gold I may perhaps consider myself fortunate. 2

Thine early Hopes are fading one by one

The brightest loftiest are the first to die

Grow faint; or cold; perish mournfully.

So in the splendor of the joyous sun

The burnished clouds do gladden all the sky

And laughing put their evening-glory on.

Till sunk the orb amid the murmuring surge:

The highest in the concave first is dead

And so successive withering to the verge

Of ocean drear—night's fall is o'er them spread

And winds and waves chaunt forth a funeral dirge.

Yet thus benighted; Youthful visions fled

One changeless hope remains to cheer my breast:

A day will dawn in the Eternal East.

Catskill [28 March 1838] 3

Find it here.